Arrival of Europeans in Africa, by Nicolas Colibert (1750 – 1806). Engraving after a drawing by Amédée Fréret, Paris, 1795 made to celebrate the first abolition of slavery on 4 February 1794 .

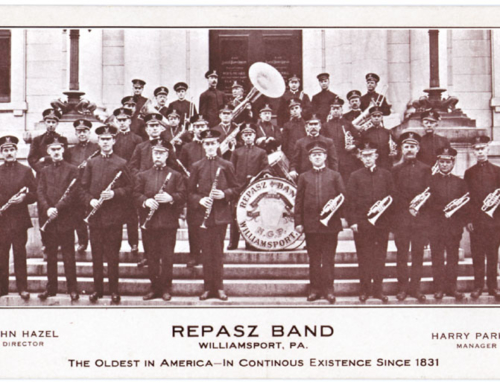

By Lou Hunsinger Jr.

Williamsport Sun-Gazette

The issue of the abolition of slavery excited great passions throughout the United States during the pre-Civil War period. Lycoming County was no exception. This was amply demonstrated in a little-known incident in April 1842 known as the “Muncy Abolition Riot of 1842.”

It is usually assumed (incorrectly) today that the people of the North were of one mind about the abolition of slavery, condemning it and working hard for its elimination. But this just was not so.

The New England states were the real hotbed for abolition, and people in states such as Pennsylvania were much more divided on the issue. A large body of opinion in this state was openly hostile to the doctrine of abolition. It was those who were openly hostile to abolition who were at the center of the “Riot of 1842.”

Enos Hawley was a Quaker, a tanner by trade and one of Muncy’s most prominent citizens. He later became its postmaster. His Quaker heritage provided him the moral base to be a strong hater of the institution of slavery. He was not shy about his revulsion of this “peculiar institution.”

In the spring of 1842 Hawley invited a speaker, whose name is lost to history, to speak in Muncy about abolition. This unknown, itinerant abolitionist speaker’s appearance was not welcomed by all. Eighteen individuals in particular met this appearance with violent anger. These men riotously attacked the schoolhouse where the abolitionist speaker was delivering an address. They pelted the schoolhouse with rocks and various other missiles, knocking out all of the windows and causing some bodily injury to the speaker and his sponsor, Hawley.

After Hawley and the speaker left the building, the men continued to pelt them with eggs. When the two got to Hawley’s house, these rowdies continued to throw objects.

The roughnecks were indicted on charges of “riotously, and tumultuously assembly to disturb and disturbing the peace of the Commonwealth in August 1842. They were placed on trial in September. That jury found thirteen of the18 guilty of the charges after much wrangling during the deliberations.

One member of the jury, ardent abolitionist Abraham Updegraff, later wrote about his experience on this jury. He described a long and contentious process in which he had to use all of his persuasive powers. The initial jury ballot came in at 11 for acquittal and one against. Updegraff argued to the other jurors that “we have been sworn to try this case according to the law and the evidence presented and that if no contradictory evidence offered by the defendants than we could nothing more but to convict them.”

Updegraff used his knowledge of German to persuade three other jurors in their native tongue to see things his way. Another poll was taken and the result showed nine for conviction and three for acquittal. Finally, on the third try, the jury reached a decision to convict

The jury’s painfully reached decision was basically annulled when Pennsylvania Gov. David Rittenhouse Porter pardoned the convicted defendants several days after the trial. His pardon message said, in part, “It is represented to me by highly respected citizens of Lycoming County, that this prosecution was instituted more with a view to the accomplishment of political ends than to serve the cause of law and order.”

Porter’s pardon message blamed the abolitionist speaker for the disorder stating that the content of the speaker’s speech was “notoriously offensive to the minds of those to whom they were addressed and were calculated to bring about a breach of the peace.”

As the result of cases like his pardon of the “Muncy Riot’ defendants, Porter was given the derisive nickname of “The Pardoning Governor.”

It is clear that the case of the “Muncy Riot” defendants had larger social and political implications. Cases like that didn’t usually receive the intervention of the governor.

This case also demonstrates the hazards that anyone involved in the Underground Railroad in the area could potentially encounter.