DUNLAP, Kansas — On a lonely country road in Dunlap, Kan., a monument to the memory of Exodusters soars. An engraved stainless steel plaque stretches between two limestone pillars and marks the family farm of a freed slave.

Built by Jack Davis, whose family bought the farm more than a century ago, the monument honors the thousands of African Americans who fled the lower Mississippi Valley for Kansas, seeking a better life.

Sometimes called “Exodusters,” a derogatory term coined by newspapers of the time, they’re former slaves who left the South in 1879 after Reconstruction failed to grant them the benefits of citizenry: the freedom to live as they chose, vote freely, and own land. Instead, Reconstruction resulted in the Black Codes, new laws that reinforced oppression, exchanging the chains of slavery for the yoke of tenant farming and sharecropping.

But more than abject poverty, Exodusters fled the anarchy and violence that followed the Civil War when marauding ex-Confederate soldiers and angry Southerners forged the Ku Klux Klan. This “tide of disorder” swept through the South, with its members stealing livestock, burning barns, and terrorizing and killing African Americans.

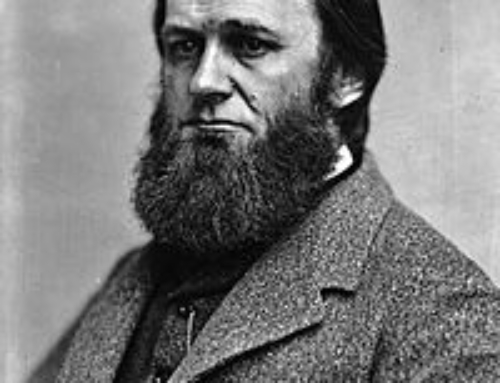

Most immigrants were spurred by word of mouth, while others followed organizers such as Benjamin “Pap” Singleton of Tennessee and Henry Adams of Louisiana. Entire communities immigrated to Kansas, “the Garden Spot of the World” and home of abolitionist John Brown.

The story of the Exodusters is a difficult one to tell because, as historian Nell Irvin Painter writes in ” Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction,” it was a movement “of poor, rural Southern Blacks not sufficiently Westernized to write their own histories,” largely ignored by scholars.

It’s an essential story to Davis, who built his monument to Kansas Exodusters and his family after a life-changing event: doctors diagnosed him with stage IV pancreatic cancer in the spring of 2010.

“My doctor finally listened to me in March 2010. She said I had spots and lesions on my liver,” Davis said. “I went to the VA (Veteran’s Administration). They said, ‘Don’t worry about your liver; you have stage IV pancreatic cancer. You have three months to live.’

“I just take life a day, a week at a time,” he said. “I have gone past the doctor’s timeline and am doing good. I could make it years longer. Not likely, but possible.”

So, with the time he had left, he built the monument, which consisted of donated steel and two massive slabs of limestone purchased from Higgins Stone Co. of Wamego, Kan. The twin, rough-hewn pillars stand 10 feet out of the ground in the garden of the former family farm, which Davis sold in 2010 to his neighbors and friends Clayton and Patricia Finney, who moved in the area as a young couple and now operate a ranching business, Wright Creek Ltd.

Davis recalled that his family raised cattle, horses, hogs, chickens, and other livestock there and grew wheat, milo, and sorghum as silage for the cattle, corn, alfalfa, and prairie hay.

“My grandfather always had a large garden. Everyone who came to our house, if they left hungry, it was their fault. I remember hearing the older folks say they starved, but if they went to the Davis place, they got full,” he said.

Davis, the son of a mixed-race couple, didn’t grow up with his mother. “My daddy never married, and I haven’t either. I was the only child my dad had. Because of racial differences, families would not let them marry.”

As a child, he called his aunt Velera Davis “Mommie,” and would listen to her stories. “Since I was a child, I listened to the older folks talk. Unfortunately, my memories of the stories and the people are vague.”

One of his favorite memories of growing up in Kansas was the sense of connectedness.

“The older people were always ‘Cousin’ or ‘Aunt.’ It seemed like a big, extended family. They’ve since moved all over the U.S. and some are quite famous,” he said.

Davis also moved quite a bit, working as a “Jack of all trades, master of none,” he said.

His experience includes stints as a roofer, farmer, painter, and mechanic. He’s driven 18-wheelers in all 48 contiguous states, as well as dump and oil field trucks. A third assistant engineer, he’s served on ships around the world, including tankers, ore carriers, dive boats, supply boats, and fish processors and catchers.

“I was going to sea making good money. While at home, I was rebuilding buildings and fences, trying to keep the place up,” he said. “Then, from 1979 to 1986, vandals destroyed the property. No one knew anything. My family tied up the farm. When I got it back, I could not rebuild. There were no others that I could pass it to that could and would successfully farm the place. I sold the family farm that my Dad and his father spent their lives building.”

A close friend’s eldest son, Terry Lyon, helped “Uncle Jack” erect the monument along Road 300, Lyon County, in Americus, Kan.

“He has been an invaluable help, loaning tools, equipment, his help, the use of his place,” Jack said. “This would have been a lot more difficult without him.”

Although it is tucked away in rural Kansas, the monument is important to Davis personally and should be important to the descendants of all Exodusters, he said.

“Very few people are even aware of the Exodusters. People forget, or deny, their history. Many have never heard of the contributions of their ancestors,” Davis said. “The descendants of the Kansas colonies have moved all over the U.S. and various countries. Some are successful; others are on welfare or in between.”

He hopes a local historical society will help preserve the monument. His lifelong friend Ustaine Talley gathered notes and oral histories for the dedication ceremony held in August 2010.

“I have tried to use durable materials so it will last for centuries,” he said. “I hope it lasts as long as the land.”

POSTSCRIPT: Jack L. Davis was born on April 22, 1932, and passed away on Monday, December 13, 2010.

A Monument to Exodusters by Robin Van Auken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at www.robinvanauken.com.

Ready for a Challenge?

Have even more fun when you accept the 21-Day Writing Sprint Challenge. This process is one I use every semester with my college students, so I know it can kickstart your creativity and introduce structure to your writing schedule. When you join my Circle of Writers & Authors, you’ll receive FREE writing resources, and you’ll sign up for my newsletter. I will not sell your information, or spam you. I will send you updates about new articles and podcasts I’ve created, and projects I’m working on. You can unsubscribe at anytime. Read my Privacy Policy here.

Wholehearted Author is for you if you are …

- Starting out as a writer and could use some guidance

- Wanting to be inspired to create and publish your book

- Looking for like-minded, happy people and helpful mentors

- Hoping to turn your writing into a full-time, awesome career

- New to the concept of “permission marketing” but willing to try

CATCH THE WEST WIND

Add WEST WIND to your library!

If you love a good mystery, a romantic whodunit that will surprise you, then WEST WIND is a great addition to your ebook library.

West Wind is my third novel as an author of Contemporary Fiction, Suspense, Thriller, and Romance. It’s FREE too, when you join my exclusive Readers Group. Join today and download your free book, and as a special thank you, you’ll receive a SECOND FREE BOOK tomorrow! The giving goes on and on when you become my fan.

When you join my Readers Group, you’ll receive updates about new projects I’m working on. You can unsubscribe at anytime. Read my Privacy Policy here.