Conflict between American Indians and white people escalated during the last two decades of the 18th century. War — both declared and undeclared — made for “dark and gloomy days,” according to historian John F. Meginness in his 1,268-page tome, “History of Lycoming County” (1892).

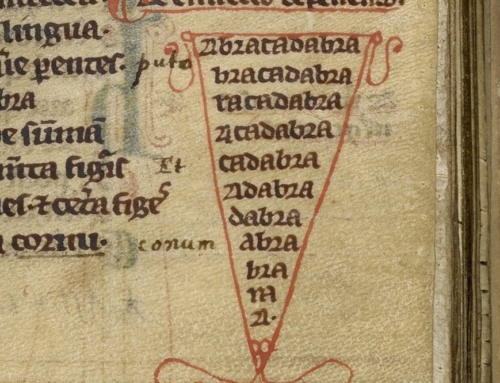

A Muncy Historical Society volunteer portrays a Colonial soldier at the grave of Capt. John Brady.

While frontier families of the West Branch Valley were “begging for help to protect them from the savages,” Meginness writes, the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania was asking for counties to furnish additional men to serve with the Continental Army under George Washington.

The settlers in America, newly declared independent, were struggling with British monarchy, and the Indians were struggling with the increasing tide of immigrating humanity, always encroaching despite land agreements.

“No one can blame the Indians for fighting to preserve their country,” writes historian Paul A.W. Wallace in “Indians in Pennsylvania” (1961). “At the same time, it is difficult to blame the settlers, caught up as they were in one of the great mass movements of mankind. That does not mean that we must condone the crimes committed by those who cheated and murdered to gain their ends. It means only that we should not be unfeeling toward either side as we look back on the clash of the races . . . ”

Attacks, Retaliations and the Brady Legend

Narratives have been published of Indian and militia attacks and retaliations. One local, quasi-famous narrative is the story of the Brady family and its enemy, Chief Bald Eagle of the Wolf Clan of Delawares.

According to C. Hale Sipe in “The Indian Chiefs of Pennsylvania” (1927), Bald Eagle “espoused the British cause, and his war parties brought death and desolation to the settlements on the West Branch of the Susquehanna.”

Historians attribute the death of James Brady to Bald Eagle, and his father, Capt. John Brady, to unidentified Iroquois Indians. And, in vengeance, Bald Eagle was murdered by the captain’s surviving son, Samuel, the “most noted scout connected with Fort Pitt during the Revolutionary War,” Sipes writes.

On Aug. 8, 1778, James Brady and four militiamen were ordered to protect a group of settlers cutting a crop about two miles above Loyalsock. The crop belonged to Peter Smith on Turkey Run, “the unfortunate man that had his wife and four children murdered about a month previous,” historians recount.

Sentinels were placed at the opposite ends of the field, and the greater part of the grain was cut. The next day, the band returned to the field to finish its work. Under cover of an early-morning fog, Indians surprised the harvesters. A brief battle ensued; James Brady was attacked and fell.

“He was so stunned with the blow of the tomahawk, that he remained powerless, but strange as it may seem, retained his senses,” writes Sipe. “They ruthlessly tore the scalp from his head as he lay in apparent death; and it was a glorious trophy for them, for he had long and remarkably red hair.”

Men cradling grain in a nearby field heard the commotion and came to assist, and the Indians retreated.

Meanwhile, James Brady, although scalped and wounded, crept and walked to a cabin where an old man named Jerome Vaness was employed to cook for the soldiers and field workers. Vaness attended to James Brady’s wounds, then mustered help from nearby Fort Muncy.

The soldiers took the younger Brady home to his mother, who “had a presentiment of something that was to happen, and being awake to alarms, met them at the river and assisted to convey her wounded son to the house,” Sipe writes. “He presented a frightful spectacle, and the meeting of mother and son is described to have been heart-rending. Her heart was wrung with the keenest anguish, and her lamentations were terrible to be heard.”

He only lived five days. The first four days he was delirious, but, on the fifth, his reason returned and he described the attack vividly. He said the Indians were of the Seneca tribe, and amongst them were Chief Cornplanter and Chief Bald Eagle.

His brother, Samuel, hastened home, but was too late. He swore vengeance on Bald Eagle and, “made a solemn vow that he would never make peace with the Indians of any tribe.”

Nine months later, Capt. John Brady was dead, shot from his horse by three Indians secreted in a thicket, Sipes writes. His body was buried in an old graveyard near Halls, where a heavy granite marker was erected, bearing the following inscription:

Captain John Brady Fell in Defense

Of Our Forefathers at Wolf Run,

April 11, 1779, Aged forty-six Years

Samuel, a Ranger at Fort Pitt, renewed his vow of vengeance on all Indians — in particular, Chief Bald Eagle. He did not have long to wait. In June 1779, a band of the Wolf Clan of Delawares and probably some Senecas, made a raid into Westmoreland County, attacking the settlement and killing people at James Perry’s Mill. The Indians also kidnapped several children.

Samuel Brady and a posse, painted and dressed like Indians, ascended the Allegheny River looking for the culprits. He suspected the Indians would be retreating to the north and probably would have canoes hidden. He was right.

Brady and his men staked out the Indian’s camp and waited for daybreak. They attacked as the first streaks of dawn floated over the verdant hills of the Allegheny,” Sipes writes, . . . “A sheet of flame blazed from the rifles of Brady and his men, and the chief of the seven Indians fell dead, while the others fled into the surrounding forest.”

Historians claim it was Brady’s own rifle that brought down the Indian chief, who was none other than Bald Eagle.

“With a shout of triumph, Brady leaped upon the fallen chieftain and scalped him. Thus, on the banks of the Allegheny, far from the harvest field near the banks of the Susquehanna where Bald Eagle killed young James Brady during the preceding summer, Captain Samuel Brady avenged the death of his youngest and favorite brother,” Sipes concludes.

The children were returned to the fort, and news of Bald Eagle’s death had the effect that the Indians made no more raids into Westmoreland that summer, Sipes writes.

Samuel Brady continued to hunt and kill Indians until his death many years later in West Virginia.

By Robin Van Auken, Williamsport Sun-Gazette