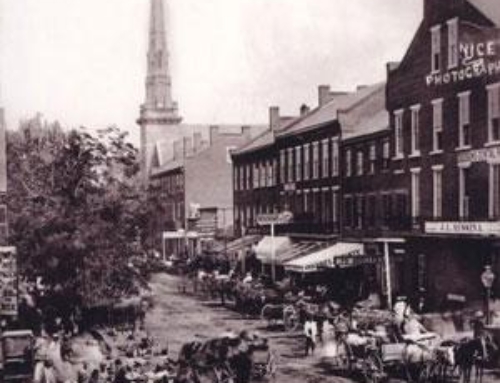

While Gen. George Washington’s Continental Army fought the British, settlers along the Susquehanna River also considered themselves at war with the displaced Indians.

Conflicts escalated daily. Rumors of a planned massacre of settlers were taken seriously.

In August 1778, the Big Runaway began along the West Branch of the river and settlers fled from their homes with barely the clothes on their backs.

That so many settlers made it to safety has been credited to Rachel Silverthorn and Robert Covenhoven.

Dubbed the “Paul Reveres of the West Branch Valley,” both Silverthorn and Covenhoven rode horses throughout the valley warning settlers of impending Indian invasion.

Evacuating the countryside was not an easy task. Everything that could float was commandeered into service as hastily constructed rafts. The women and girls manned the rafts, while the men and boys walked the shores, driving cattle and warding off Indians.

It was a tragic sight, eyewitnesses reported. One settler, Anna Jackson, recounted that all roads leading to the river were crowded with women and children fleeing the valley.

“You may as well try to count the raindrops in a cloud as to try to count them,” she says in an account printed in the Muncy Historical Society’s quarterly publication, “Now and Then” (1971).

The Big Runaway sent frightened convoys of settlers fleeing to Forts Muncy, Freeland and Augusta as Indians sought vengeance throughout Northcentral Pennsylvania.

Rachel Silverthorn

Silverthorn is an extraordinary woman, claims Katharine W. Bennet in the Lycoming County Historical Society Journal (Winter-Spring 1970-71).

“Many heroic women feature the frontier life of the state, but none excel in sheer bravery as Rachel Silverthorn,” Bennet writes. “Mollie Pitcher operated a cannon at the battle of Monmouth, in place of her wounded husband, and Margaret Corbin, another Pennsylvanian, filled the place of her husband who had been killed at the siege of Fort Washington. But Rachel Silverthorn emulated Paul Revere . . . Rachel’s ride was to save her unsuspecting neighbors who lived along the half-beaten trail that followed Muncy Creek.”

The Silverthorns were early settlers in Muncy Township and had been in Fort Muncy on Aug. 8, 1778, when Continental soldiers, protecting farmer Peter Smith while he reaped his rye fields, were attacked by Indians. Among the soldiers was young James Brady, who was shot, wounded with a spear and scalped by Chief Bald Eagle.

Capt. John Brady, father of James, was at the fort when the retreating soldiers brought news of the attack.

“Brave soldier that he was, he controlled his own anxiety and grief and thought of the safety of other harvesting bands that had gone from the fort that morning,” Bennet writes. “He had the call of arms sounded and the little garrison was mustered on the parade ground in front of the fort.”

The captain had his favorite horse saddled and asked, “Who will volunteer to carry the news of danger to our friends?” Bennet writes.

No one stepped forward.

Capt. Brady raged, “This very night the wily varmints may creep up and when the first gleam of light shines over Muncy Hills, the scalping knife and tomahawks will again be flourished over their defenseless heads,” Bennet reports. The grief-stricken Brady thundered, “Who will go on this errand of mercy?”

According to Bennet, “a gentle voice on his right” volunteered.

“I, Captain, I will tell them of their danger. I know the trails full well; I can make the circuit of the Gortners, John Alwood, the Shaners, David Aspen and the Robbs,” Bennet writes of Silverthorn.

“And suiting the action to the word, Rachel Silverthorn sprang into the saddle and, before the soldiers had time to recover from their astonishment and chagrin, was flying with the speed of the wind toward the nearest cabin on the creek,” Bennet continues. “Her timely warning was heeded, for under the cover of the dark night that followed, every exposed settler was safely housed in the fort. As for the brave Rachel, her return from the perilous mission was made as the captain predicted, before the last rays of sun vanished behind the Bald Eagle.”

Even after Indian troubles depopulated the valley, the Silverthorn family made an early return, erected a temporary shelter on the charred remains of their log cabin and made an effort to harvest their ripening grain fields.

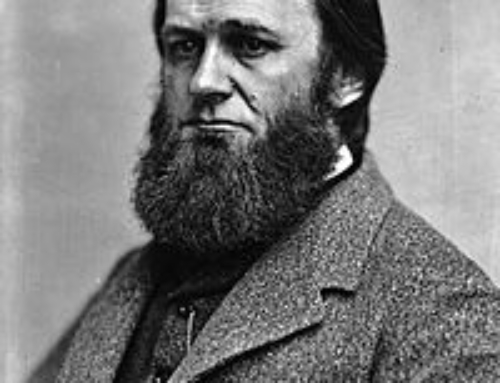

Robert Covenhoven

Covenhoven was a highly regarded scout, spy and guide. He was born “of Low Dutch parents in Monmouth County, N.J. He was much employed during his youth as a hunter and axeman to surveyors of land in the valleys tributary to the North and West Branches of the Susquehanna,” writes Carlton E. Fink Sr. in Lycoming County Historical Society’s Journal (Summer 1967).

He knew all of the paths in the wilderness, an attribute that made him useful as a scout and guide to the military parties of the Revolution.

Covenhoven, Fink writes, ” . . . was fearless and intrepid, he was skillful in the wiles of Indian warfare and he possessed an iron constitution.”

He joined the campaigns under Gen. Washington and fought at the battles of Trenton and Princeton.

In the spring of 1776, Covenhoven returned home, “where his services were more needed by the defenseless frontier,” Fink writes.

By the spring of 1778, murders of settlers prompted orders to evacuate Fort Muncy. Settlers were to seek refuge in Sunbury.

No one would volunteer to carry the message to Fort Muncy except “Covenhoven and a young Yankee millwright,” Fink continues.

Reports were occasionally made of Covenhoven skirmishing with Indians, but after hostilities ceased, “our hero dropped from public view,” Fink writes. “His efforts in behalf of his neighbors were Herculean, when the emergencies demanded courage and skill; but as soon as the necessity for him had passed he modestly retired into oblivion, and never sought, at the hands of those he had so faithfully served, any recognition of his services.”

In 1832, he applied for a government pension for his services in the border war.

His great-grandson, W.H. Sanderson, writes in the Lycoming County Historical Society Journal (Spring 1969), of his first meeting with Covenhoven. Sanderson recalls the man as being tall with long, gray hair streaked with red.

“He wore his hair straight down and combed it back over his ears. His eyes were brown and he had a florid complexion and a prominent nose,” Sanderson recalls. “I was a little shy of him, as my mother had told me he was a great Indian Killer. But, after being around him for four or five days, I soon became very fond of him, as he was like an old soldier who always wanted to talk.

Sanderson remembers Covenhoven’s black hunting knife.

“On the back of this knife were filed 12 or 13 notches, and each notch represented an Indian killed by him,” Sanderson writes.

“The gun used by Covenhoven was an old flintlock, with a barrel six feet long. I asked if the gun ever misfired, and he told me, “Never when it was needed.'” The kind, old man was interesting, Sanderson writes, “and he and I sat by the hour over the high banks of the river talking about his many adventures.”

Covenhoven died in October 1846, at the age of 90, and was buried in a graveyard in Northumberland.

By Robin Van Auken, Williamsport Sun-Gazette