Destinations to Honor the Torn Country’s History

When planning a trip to Ireland, don’t forget destinations that honor the torn country’s history.

A cannon protects the coastline of Dun Laoghaire, County Dublin, Ireland.

Why “torn country,” you ask?

Ireland is a country that’s been struggling with its identity – one separate from Great Britain – for more than a century. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces fought the Irish War of Independence from 1919 to 1921.

Geographically, it is an island in the North Atlantic, separate from Great Britain.

Religion also plays into the rift, with Northern Ireland, and in particular in Tiger’s Bay in north Belfast, where employment opportunities seemed to favor Protestant workers over Catholic during “The Troubles,” which lasted three decades. The shipyards there once employed tens of thousands of predominantly Protestant workers; however, unemployment has leveled the playing field. The predominant religion in the Republic of Ireland is Christianity, with the largest church being the Roman Catholic Church.

Politics divide the country into the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. Even decades after the Good Friday peace agreement, Northern Irish politics are dominated by nationalism and unionism, a power-sharing model of democracy designed for societies where there has been, or is the potential for conflict. Some people are predicting violence because of Brexit, claiming that a hard Brexit and borders between the two regions of Ireland could see a return to violence.

Third Tipperary Brigade Flying Column No. 2 under Seán Hogan during the War of Independence. Most of the IRA units in Munster were against the treaty.

Civil War

While in Ireland, you may hear some people hum the “Foggy Dew,” but don’t be alarmed – they’re not angling for conflict. They’re keeping the memory alive that young Irish men should have been fighting for their independence during World War I, rather than support Great Britain. Fr. Charles O’Neill, a curate at St. Peter’s Cathedral, Belfast, wrote the song’s lyrics, echoing the sentiment, “‘Twas better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Sulva or Sud El Bar.“

Late popularized by Sinéad O’Connor and Paddy Moloney of the Chieftains, the song chronicles the events of April 1916 when patriots led by James Connolly and Patrick Pearse proclaimed the Irish Republic and launched the Easter Rising against British rule. Great Britain crushed the rising in one week, and its commanders imprisoned and executed. The harsh response engendered support for Irish independence and in the December 1918 election, the republican party Sinn Féin won a landslide victory, and the uneasy Anglo-Irish Treaty led to the ensuing Irish Civil War

Listen to an instrumental version of “Foggy Dew.”

Listen to Sinéad O’Connor and The Chieftains perform the “Foggy Dew.”

The Troubles

Although the destinations recommended in this article are in the Republic of Ireland, if you decide to travel north and visit Belfast, you should understand the historical importance of “The Troubles,” which began during a campaign by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association that sought to end discrimination against the Catholic/nationalist minority.

During the late 1960s and early ’70s, NICRA members protested against the Protestant/unionist government and police brutality. Rising tensions led to violence in 1969, and the deployed British troops built “peace walls” to keep the two communities apart.

The army soon came to be seen as hostile and biased, particularly after Bloody Sunday (also the Bogside Massacre), when on January 30, 1972, British soldiers shot 28 unarmed Catholics during a protest march against internment. Fourteen people died while fleeing and while trying to help the wounded. Rubber bullets and batons injured others, and two people were run down by army vehicles.

The Troubles “officially” ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

Another song that has ear-wormed its way into the Irish political landscape is U2’s 1983 anthem “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” Despite its militaristic drumbeat and rousing lyrics, lead singer and co-writer Bono (Paul David Hewson) has always claimed is “… not a rebel song.”

Listen to U2 perform “Sunday Bloody Sunday.”

Present-Day Ireland

Dublin Castle

Today, most visitors begin their tour of Ireland in the global city of Dublin, founded in the 7th century by Gaels, then expanded into the Kingdom of Dublin by Vikings.

Ranked as an “Alpha” city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC), it is one of the top 30 cities in the world today.

Cultural divides still exist; however, with Dublin being split along a north-south axis by the River Liffey. Traditionally, Northside is considered a working-class to the middle-class area, and Southside is seen as middle class to upper-middle class.

Cultural “quarters” or districts also divide Dublin. These are of importance to tourists and include the:

- Medieval Quarter – Dublin Castle, Christ Church and St Patrick’s Cathedral and the old city walls

- Georgian Quarter – St. Stephen’s Green, Trinity College, and Merrion Square

- Docklands Quarter – Dublin Docklands and Silicon Docks

- Cultural Quarter – around Temple Bar

- Creative Quarter – between South William Street and George’s Street

Keep these areas in mind when you plan your walking tour of Dublin. When traveling beyond Dublin, consider using public transportation or small tours for coastal visits. Now that you know the history of this torn country, you can appreciate not only its natural beauty but its significant historical landmarks.

Walking Downtown Dublin

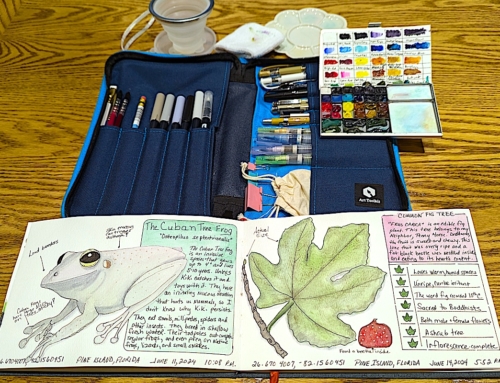

Molly Malone Statue

The Molly Malone statue, crudely known locally as “The Tart with the Cart,” was installed during the 1988 Dublin Millennium celebrations, when 13 June was declared to be Molly Malone Day. The statue was presented to the city by Jury’s Hotel Group because “Molly Malone” (also known as “Cockles and Mussels” or “In Dublin’s Fair City”) is a popular song, which has become the unofficial anthem of Dublin. The song is a fictional tale of a fishmonger who sold seafood on the streets of Dublin, but who died young, of a fever. She is typically represented as a hawker by day and part-time prostitute by night. Her statue has moved to Suffolk Street.

Justice at Dublin Castle

Justice is another controversial statue in the city, which stands above the Cork Hill entrance to Dublin Castle. Many icons have Justice blindfolded, but in this case, Iustitia’s eyes are open. Since the 15th century, the blindfold has represented objectivity and impartiality. This statue also holds scales, tilted toward the Dublin’s Tax Office. Her sword, which typically points downwards, is held upright and she looks at it with a knowing smile.

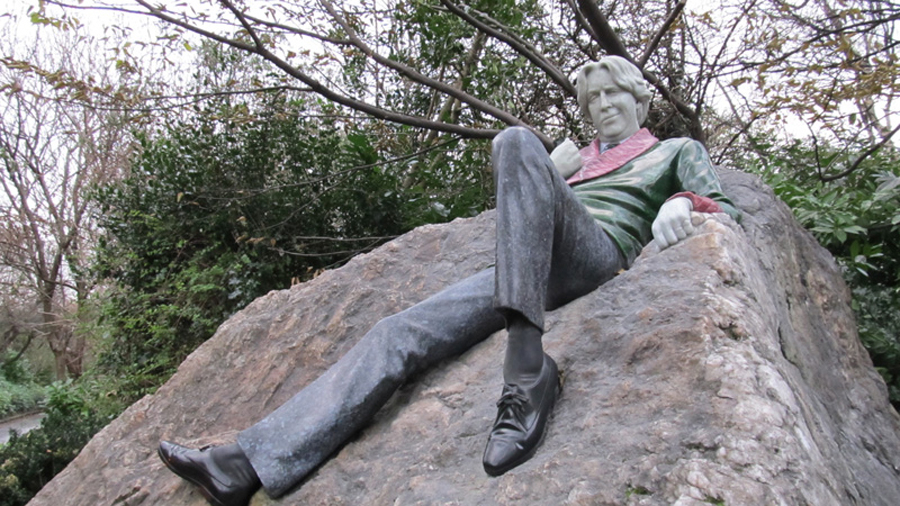

Oscar Wilde Statue in Merrion Square

Designed by artist Danny Osborne, this statue is one of three in a Memorial Sculpture Collection in Merrion Square that commemorates Oscar Wilde. The Irish poet/playwright reclines inside the park, on a quartz boulder. Wilde looks at his boyhood home where he grew up. A controversial, yet famous and beloved writer, he was arrested in 1895 and convicted for “gross indecency with men.” He spent two years at hard labor, the maximum penalty. On his release, he moved to France, where he wrote his last work, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” (1898), a poem about harsh prison life.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral

Founded in 1191, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin is the National Cathedral of the Church of Ireland. One of the most popular destinations for tourists to Ireland, the Cathedral is located on the holy site of a well where Saint Patrick baptized Christian converts for more than 1,500 years. The present Cathedral building, in terms of shape and size, dates from 1220-1259. It is made from local limestone and imported stone from Bristol. It is also the tallest church in the country, with its 43-meter spire.

National Botanic Gardens

The National Botanic Gardens were founded in 1795 by the Dublin Society and hold 20,000 living plants and many millions of dried plant specimens. The gardens, placed into government care in 1877, include glasshouses of architectural importance, such as the Palm House and the Curvilinear Range. Today the Glasnevin gardens are free of admission and serve as a center for horticultural research and training, including the breeding of many prized orchids.

Glasnevin

Glasnevin Cemetery is the first burial ground for Irish Catholics in Dublin, because of the repressive Penal Laws of the eighteenth century. Daniel O’Connell, champion of Catholic rights, launched a legal campaign and proved that no law existed that forbid praying for a dead Catholic in a graveyard. O’Connell pushed for the opening of a burial ground in which both Irish Catholics and Protestants could give their dead dignified burial, and Glasnevin Cemetery opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of many of Ireland’s most prominent national figures, including Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, Michael Collins, Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, Maude Gonne, Kevin Barry, Roger Casement, Constance Markievicz, Pádraig Ó Domhnaill, Seán MacBride, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, James Larkin, Brendan Behan, Christy Brown and Luke Kelly of the Dubliners.

Kilmainham Gaol

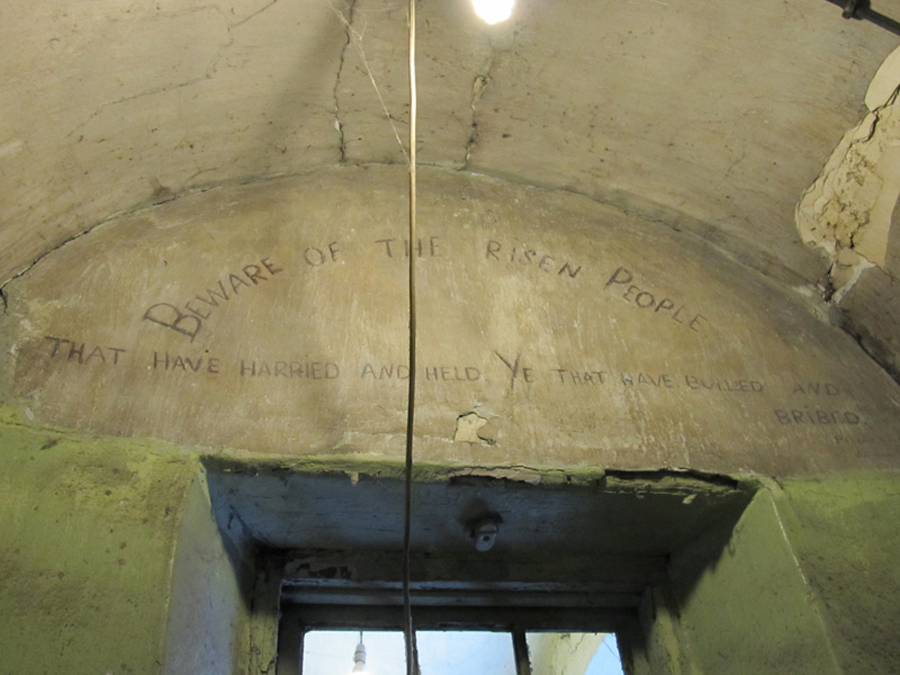

Graffiti was drawn and etched in the walls of Kilmainham Gaol, marking the passage of people through the historic prison. Some graffiti was placed to be read by prison officers as well as prisoners, including this quotation by Padraig Pearse above a doorway leading into the so-called “1916 Corridor.” Pearse along with his brother and 14 other leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising were executed by firing squad at Kilmainham.

The Rebel

by Patrick Pearse

A leader of the Easter Rising in 1916, Patrick Pearse was an orator, teacher, barrister, poet, writer, separatist nationalist and political activist. Pearse, along with his brother and 14 other leaders of the rising, was executed by firing squad. Pearse came to be seen by many as the embodiment of the rebellion.

I am come of the seed of the people, the people that sorrow;

Who have no treasure but hope,

No riches laid up but a memory of an ancient glory

My mother bore me in bondage, in bondage my mother was born,

I am of the blood of serfs;

The children with whom I have played, the men and women with whom I have eaten

Have had masters over them, have been under the lash of masters,

and though gentle, have served churls.

The hands that have touched mine,

the dear hands whose touch Is familiar to me

Have worn shameful manacles, have been bitten at the wrist by manacles,

have grown hard with the manacles and the task-work of strangers.

I am flesh of the flesh of these lowly, I am bone of their bone I that have never submitted;

I that have a soul greater than the souls of my people’s masters,

I that have vision and prophecy, and the gift of fiery speech,

I that have spoken with God on the top of his holy hill.

And because I am of the people, I understand the people,

I am sorrowful with their sorrow, I am hungry with their desire;

My heart is heavy with the grief of mothers,

My eyes have been wet with the tears of children,

I have yearned with old wistful men,

And laughed and cursed with young men;

Their shame is my shame, and I have reddened for it

Reddened for that they have served, they who should be free

Reddened for that they have gone in want, while others have been full,

Reddened for that they have walked in fear of lawyers and their jailors.

With their Writs of Summons and their handcuffs,

Men mean and cruel.

I could have borne stripes on my body

Rather than this shame of my people.

And now I speak, being full of vision:

I speak to my people, and I speak in my people’s name to

The masters of my people:

I say to my people that they are holy,

That they are august despite their chains.

That they are greater than those that hold them

And stronger and purer,

That they have but need of courage, and to call on the name of their God,

God the unforgetting, the dear God who loves the people

For whom he died naked, suffering shame.

And I say to my people’s masters: Beware

Beware of the thing that is coming, beware of the risen people

Who shall take what ye would not give.

Did ye think to conquer the people, or that law is stronger than life,

And than men’s desire to be free?

We will try it out with you ye that have harried and held,

Ye that have bullied and bribed.

Tyrants… hypocrites… liars!

Around Ireland

New Grange

Older than Stonehenge, and even the Egyptian Pyramids, Newgrange is a Neolithic monument. Its proper name is Brú na Bóinne, which means the “palace” of the Boyne, referring to its location within the bend of the River Boyne. A passage tomb, it was built around 3200 BC, used for several hundred years, then was lost to time until quarrying activities in 1699 led to the rediscovery of the passage and chamber. Major archaeological excavations, followed by conservation and presentation led to its status as a World Heritage Site today, close to the village of Donore, and visitors may enter the tomb only during formal tours, which leave from the Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre.

Howth

Ireland’s Eye is a small island and bird sanctuary near Howth, an Irish village east of Dublin. A clifftop trail has sweeping sea views, and sailboat racing on the calm waters here are a favorite pastime, year-round. Visitors may take a train from Dublin and while in Howth, tour the rhododendron gardens on the grounds of 15th-century Howth Castle. The 19th-century Martello Tower here is famous as the location where the fictional Leopold Bloom proposes to Molly in James Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

Galway

Galway is another harbor city on Ireland’s west coast, and the city’s hub is 18th-century Eyre Square. This popular spot features shops and traditional pubs that offer live Irish folk music. The Latin Quarter, which retains portions of the medieval city walls, is nearby and is filled with cafes, boutiques and art galleries. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay and is the sixth most populous city in Ireland. A notable visitor, Christopher Columbus visited Galway in 1477.

Cobh in County Cork

Cobh in County Cork was often the last glimpse that millions of Irish had of their homeland before immigrating to America, or those deported to Australia. Its harbor offered natural protection, and by the 19th century, the town became prominent as a tactical center for naval military base purposes. On April 11, 1912, it was the final port of call for the RMS Titanic before she set out across the Atlantic on the last leg of her maiden voyage. A German U-boat sank the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, and rescuers brought the survivors and the dead to Cobh. Many are buried in the Old Church Cemetery there.