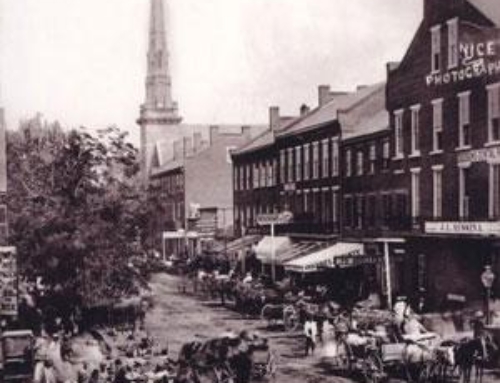

Historical preservation is an admirable, though challenging, goal to achieve. Preservation works best in communities that have programs managed at the local government level.

In 2003, Williamsport’s City Council considered an amendment to a zoning ordinance that would result in new historic preservation sections within the city, as well as regulate and protect properties outside the Historic District. The ordinance, however, did not pass, and consequently, historic property has been lost to commercial development. One such piece of property is the Thomas Lightfoot Inn, once a colonial-era farmstead.

In April 2004, the Lycoming County Historical Society contacted Lycoming College’s archaeology department, requesting a cultural resource management survey at 2887 South Reach Road, Williamsport, PA, the site of the inn. The landowner, Bernard D. Rell, purchased the property in 2003 after a fire in 2002 destroyed the historic structure. Rell planned to build self-storage units on large concrete slabs. He hired a contractor to clear and grade the land, a gentle slope filled with 200-year-old trees, winding brick paths, and historic debris.

Reach Road neighbor and activist Alden Seitzer protested Rell’s plans to develop the area for a commercial enterprise. For several months, Seitzer lobbied the City of Williamsport to deny Rell building permits and to protect the historic site. Encouraged by another neighbor who lives in the only remaining structure of the Long Reach farm, a log granary (ca. 1788), Seitzer contacted city and state officials, non-profit historical preservation organizations, and the media. He contended that, based upon a 1936 archaeological excavation by Harry L. Schoff of the Works Progress Administration, the site was historically significant and contained Native American graves. Schoff recovered five historic burials that he identified as Indian, as well as numerous artifacts. Schoff concluded that the skeletons were not remnants of an Indian village based upon the associated artifacts. He proposed that they “could have been members of a raiding party against the settlers and were worsted in the fight.”

Derek (a.k.a. Derrick) Updegraff purchased Long Reach in 1788. His brother, Thomas Updegraff, settled the land in 1789. Thomas arrived at Long Reach with only twenty-five cents, a wife, and two children. He immediately began working, trading leather for iron and selling both. Around 1792, the original log homestead burned, and Thomas built a new, larger home approximately 240 feet west of the old one. His plantation eventually included a barn (said to be the largest in the area), a smokehouse, a springhouse, and a granary, all of which still stand.

According to eyewitness accounts, the new Long Reach homestead featured two historic tunnels that connected the farm and the granary to the West Branch Canal, which was built in the 1830s. The Updegraffs used the tunnels to transport products from the canal boats to the farm.

As they were abolitionists and Quakers, the family also used the tunnels to shuttle runaway slaves to freedom along the Underground Railroad. In the documentary film, “Follow the North Star to Freedom,” viewers see a tunnel leading away from the house through the basement. Former owners have reported a three-foot-tall void between the second and third floors. A common belief is that runaway slaves hid there. Other histories report that the Updegraffs hid slaves in the smokehouse, springhouse, and other outbuildings.

In a memoir about his father, “The Life of Thomas Updegraff,” Abraham Updegraff writes, “Father was for many years the agent at this station of the U.G.R.R., and as this railroad failed to make annual reports, we shall add a short description of its workings. Although there has (sic) been several very narrow escapes, this station never lost a passenger. No slave was ever reclaimed after once reaching here by this route.”

Thomas Updegraff also accommodated canal travelers, converting his home into an inn. The inn had ten rooms, five bathrooms, and a kitchen. The granary served as a stable for the mules that pulled the packet boats.

The Updegraffs also owned a schoolhouse west of the property. According to a Williamsport Sun report on June 4, 1954, many “Indian arrowheads and cooking utensils have been found around the school house.”

In December 1936, Works Progress Administration archaeologist Harry L. Schoff excavated five historic-period Native American burials on the property near the foundation of the schoolhouse. Schoff observed trace amounts of wood and nails in the soil, which led him to speculate that the bodies were buried in wooden boxes. Along with the skeletal remains, Schoff found metal objects and beads, bringing him to the conclusion that the Native Americans were of the contact period and probably Shawnee.

In 1936, Laura Updegraff died. Upon her death, Mr. H. Merrill Winner bought out the remaining heirs, acquiring their property (232 acres, compared to the original 313 acres). His wife, the former Kathryn Bennett, was a descendant of the original Updegraff family. During the period that Winner owned the property, he had the front porch and the second-story shutters removed. The original barn burned down during the 1920s; in 1939, it was rebuilt east of its original location. Winner also built a five-car garage.

In 1954, Winner sold the property to Nelson U. Phillips of Boston. This event marked the first time in its 162-year history that a member of the Updegraff family did not own the property known as “Long Reach.” Phillips then sold the land to Charles Bidelespacher, who parceled the land into river lots and industrial development. The farmhouse, now a rental property, fell into disrepair.

In 1986, James and Rita Chilson purchased the property. The Chilsons were aware of the property’s historical significance and invested thousands of dollars in restoring it as a bed and breakfast. The Chilsons named the house the “Thomas Lightfoot Inn” after the man who initially surveyed the land. In 1989, the Chilsons applied to the National Register of Historic Places to have the property listed. They were denied because of modern renovations.

In 1997, the Chilsons sold the property to Michael Chelentis, who in turn sold his interest in 1999 to Alex and Donna Kadenas. The Thomas Lightfoot Inn struggled economically until January 2002, when a late-night fire gutted the structure.

Rell purchased the property in 2003 and applied for permits to begin construction of storage units.

In August 2003, Jean Cutler, Director of the Bureau for Historic Preservation at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, contacted the City of Williamsport regarding the planned construction. The purpose of her communication, she outlined, “is to inform you that significant cultural resources are located on this site, which may be eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. The Updegraff Site will contribute significant information to our knowledge of the history of Lycoming County, the early development of Pennsylvania, and the role of Williamsport in the abolitionist movement.”

She concluded, “We hope that the Planning Commission can work with the developer so that these resources can be avoided.”

In addition to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, the Indian Country Today news service, the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania, and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Association all sent letters urging the City of Williamsport and other officials to prevent the destruction of the site.

In response, Williamsport’s City Council imposed a 90-day moratorium during which the city codes staff had the power to deny building and demolition permits for properties that may have historic significance. The council reviewed the city zoning ordinance in fall 2003, considering a revision to benefit historic preservation. It would also regulate and protect properties outside the Historic District. However, as noted earlier, the council decided not to alter the zoning ordinance and granted building permits to the contractor.

In March 2004, City Engineer John J. Grado contacted Rell, requesting that he consent to three requests made by the City Council on behalf of the Lycoming County Historical Society. The Historical Society sought access to the property to scan the site for subsurface voids or tunnels. It also requested that Lycoming College’s archaeological department be allowed to excavate a series of test pits as part of an abbreviated investigation, and that a local archaeologist be allowed on the property during commercial excavation to observe and document any historical evidence uncovered.

Rell agreed, and, on April 17, 2004, members of the historical society and local archaeologists mapped and remotely scanned the site.

In May, Lycoming College students created a research design and conducted a week-long cultural resource management project. The purpose of their project was twofold: The City of Williamsport requested an archaeological investigation of the property to recover and record artifacts of prehistoric and historic significance and report its findings to the Historical Society for future scholarship; and to respond to the public demand for action prior to destruction of a cultural landmark.

Many of the area’s residents have celebrated birthdays, weddings, anniversaries and other special occasions at the historic Thomas Lightfoot Inn. They mourned the loss of this nostalgic and beloved attraction. Lycoming College’s research, well documented by the mass media (newspapers, radio and television), and subsequent report is intended to provide solace and closure to people concerned about the former Long Reach farm and popular tavern.

Survey and Excavation at Long Reach, Thomas Lightfoot Inn

On April 17, 2004, members and staff of the Lycoming County Historical Society met with archaeologist William Lowthert of R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates, Inc. (Frederick, Md.) at the Long Reach property. A geophysical remote sensing expert, Lowthert had volunteered his services to benefit the historical society. Using a conductivity meter, Lowthert scanned a portion of the property at 2778 South Reach Road. According to his subsequent report, earth conductivity and magnetic susceptibility surveys were undertaken within a 70 x 40 meter (229.7 x 13.2 ft) area that society members indicated might be historically significant.

Prior to the geophysical investigations, archaeologists used a 50-meter surveyor tape and a compass to establish a grid within the project area. Remote sensing lanes were spaced at 1 m (3.28 ft) intervals. Lowthert took readings every .5 m (1.64 ft) along these lanes.

According to Lowthert’s report, the survey identified a series of anomalies characteristic of structural remains at other historic period sites. Strong signals along the western edge of the survey area represented the Lightfoot Inn footprint.

Other anomalies were associated with an old road or gravel path, a brick path, and small outbuildings such as privies or a kitchen midden. No patterning could be identified within these anomalies, Lowthert reports, to suggest concentrated prehistoric burials, although a few subtle anomalies in the southeast portion of the survey area could have been related to prehistoric features.

Remote sensing did not detect the tunnel because it is probably located outside of the area designated for survey. A long-time employee of a commercial business west of the property verified the existence of a tunnel. He told archaeologists that he had been inside the basement and in the entrance of the tunnel during the 1990s before James Chilson sold the property. He said the tunnel would have been at the west-northwest side of the Lightfoot Inn structure, which fell outside of Lowthert’s survey area. The Rev. Dr. John Piper, dean of admissions at Lycoming College and a published historian, supported this claim. Piper said he had been in the basement of the Lightfoot Inn and had seen the tunnel.

Mary Elizabeth Winner Stockwell, a direct descendant of Abraham Updegraff, lived in the house until it was sold out of the family. She remembers a tunnel in the basement, and, in a 1993 interview, described it as leading to a smokehouse. It had been walled off several feet inside the doorway to make a room-sized place, with the modern blocks clearly differing from the rest of the construction.

On May 7, 2004, Lycoming College archaeologist Robin Van Auken visited the Thomas Lightfoot Inn site and spoke with Toby Edwards of J.F. Chenault Construction. Edwards reported that he had been working at the site all morning with crawler dozer removing tree stumps, concrete foundations and brick pathways, leaving in his wake “basements” or craters that may have reached depths of more than 18 inches. Unaware of the impending archaeological investigation, he had removed many of the pin flags placed by Lowthert. None of the previously mapped features still existed.

Daniel Vassallo of Vassallo Engineering and Surveying, Inc., a Williamsport-based firm, provided Van Auken with a new survey map, minus Rell’s land-use design.

On May 10, Van Auken and the Lycoming College archaeology crew visited the Thomas Lightfoot Inn site. Again, contractors were dozing topsoil, and excavating tree stumps, concrete, bricks and artifacts, piling them into small hills along the northwest boundary of the property. The archaeology investigation was slated to begin May 12, but much of the site had already been destroyed. Rell’s contractors agreed to temporarily halt work so that the archaeology crew would have several uninterrupted days at the site.

On May 12, the Lycoming College archaeology crew, consisting of instructor Van Auken, Michelle Burns, Yvette Andrews, Megan Hall, Erin Hocker, Matthew Stackhouse and Eryn Woleslagle, reported to the Thomas Lightfoot Inn site. The crew re-mapped the site using two of Lowthert’s original pin flags. The crew used a systematic survey of 50 x 50-65 cm test pits spaced 30 feet (9.144 m). Working in pairs, the students dug 18 test pits in varying soil conditions – some with sand, gravel or hard clay. Finds included a prehistoric side-notched net sinker, historic pottery, brick, nails, wire, soil, glass shards, a coin (1838 U.S. one cent), and bone.

The contractors unearthed the bone while removing a tree stump. At the request of city engineer John Grado, archaeologists were to report any potential human remains to the Williamsport Police and the county coroner. The bone appeared to be the top of a femur, but it was unclear to the crew if the bone were human. Van Auken sent the bone to Dr. Pamela Harrington of Cornerstone Family Health Center, Williamsport, for a professional opinion. Harrington could not rule out the possibility the bone was human. Next, orthopedic surgeon Dr. Tom Connelly of Susquehanna Health Systems examined the bone. He and a colleague both said the bone could be human, but they were unsure. Van Auken sent the bone to the county coroner. In all, the coroner, several orthopedic surgeons, physicians, anatomists, veterinarians, and even butchers, assessed the bone. Despite conflicting opinions, the consensus was that the bones were most likely of a “large mammal,” but probably not human.

On May 13, the archaeology crew returned to the site and recovered more historic and several diagnostic prehistoric artifacts. It was concluded that the prehistoric artifacts (an Archaic projectile point, a drill, and a net sinker) were not in situ and may have been part of dirt fill carted in from the banks of the river nearly two centuries before. The crew expanded Test Pit 21 where the bone had been founded the previous day. More bone fragments were recovered 12 inches below the surface.

On May 14, the crew returned to Test Pit 21 widening the unit to 5′ x 5′, digging arbitrary levels of 10 inches by quadrants. More historic artifacts, including a clay pipe stem and several bowl fragments, were recovered in the north-center of the unit about 10 inches from the surface. A Late Archaic chert projectile point (Genessee, 5000-3500 YA), was found in the northeast quadrant near the surface.

The crew also expanded Test Pit 34, which yielded the prehistoric net sinker, into a 5′ x 5′ excavation unit. At a depth of five inches in the northeast quadrant, two animal teeth (one incisor and one molar) were found.

On May 15, archaeologists put in six shovel test pits at the east end of the property in an attempt to locate evidence of the original Updegraff log cabin. The contractors had not yet disturbed the area. The first two test pits, UH1 and UH2, reached 50 cm with few cultural remains found. In UH3, a five cm level of freshwater mussel shells and charcoal was found at a depth of 60 cm. Beneath the charcoal layer was an orange clay/sand matrix. In this clay/sand matrix in UH3, archaeologists recovered a rusted metal door pull, fragments of glass and indeterminate metal and some stone. At a depth of 85 cm, the crew struck a large, flat stone.

In UH4, 6 meters east of UH3, the charcoal and shell appeared at 46 cm, however, there was less shell and charcoal. The crew encountered the same large, flat stone at the bottom of the test pit, a depth of 51 cm, and again, it covered the bottom of this test pit. It is possible that the stone had supported the original log structure, or may have been a stone floor.

UH5 yield no artifacts except for a bit of charcoal at 50 cm and a layer of grey ash with mussel shells at 65 cm. The pit depth measured 70 cm.

Test Pit UH6 was similar to the other pits; at 51 cm, several smaller flat rocks were recovered, then at 60 cm the edge of the large flat rock. Small amounts of charcoal and freshwater mussels were recovered.

On May 17, the archaeology crew returned to the site to complete and close the two expanded test pits, 21 and 34. In 21, historic pottery, indeterminate metal fragments, and another piece of a clay pipe bowl were recovered. The stratigraphy was mottled; the soil was orange-brown with black leaching. There was much disturbance and grass was found in the north part of the unit at a depth of 40 cm. It was conjectured that the contractor, while removing a tree stump, had disturbed the entire unit.

Conclusion

The historic property of the Long Reach, one of the oldest farmsteads in Williamsport and possibly Lycoming County, has been impacted by destruction and construction for more than 60 years, beginning with the building of the dike along the West Branch of the Susquehanna River.

All of its original buildings have either burned, been dismantled or collapsed because of decay, with one exception – the log granary presently owned by Anna Kramer. Before the property at 2728 Reach Road was destroyed, archaeologists were able to map some of its original features and were able to collect a sample of historic and prehistoric artifacts. These artifacts are important in the telling of a colonial family’s struggle from poverty to prosperity.

Thomas Updegraff and his family probably built their original log structure directly north of the existent log granary. In the early 1800s, this structure burned. Whether it was intentional is unknown. Only a few historic artifacts were found in the ash layer, approximately 50 cm below the surface level. This may be an indication that the fire was planned and the Updegraff’s personal property had been removed from the structure before it burned. The soil was then “sweetened” by the addition of freshwater mussels, a rich source of calcium and nitrogen for growing crops.

The Updegraffs mounded the farmstead to the west to protect their property from the seasonal floods, bringing in wagonloads of soil from along the nearby riverbank, a matrix also rich in nutrients. A stone wall wrapped around the Updegraff’s new house, and a slate step led to the front entrance. A row of hardwood trees completed the avenue. Later, they added a brick walkway, winding through the property, possibly from small gardens to various outbuildings.

When the Updegraffs built an addition to the home, once again soil from the river was brought in by wagons and piled up along east side of the stone wall. The land was leveled with the top of the wall, approximately three feet high.

Prehistoric Indian artifacts – a late Archaic point, a drill, a net sinker and several chert flakes – were probably transported to the site in this matrix. This may be the reason why no other Indian artifacts were recovered (when one netsinker is found, others should be nearby). In addition, the lack of Indian pottery, the presence of the Genessee Late Archaic point and the netsinker and the drill (which are not diagnostic) indicate that the soil that the Updegraffs used to mound the homestead probably came from an Archaic Indian site along the river.

Historians know that the Updegraffs and their heirs lived at Long Reach from 1788 throughout the mid-1900s. The historic artifacts recovered verify occupation of the farm from the late 1700s to the late 1800s. Among the most significant, datable artifacts were an 1838 coin (minted at the height of the Canal Period), white ironstone china sherds (mid-late 19th century), blue transfer ware sherds (late 19th century), brown stoneware sherds, cut nails (ca. 1820-1900) and pane glass.

Although archaeologists hoped to find evidence of the house foundation and tunnels, contractors had already removed all foundational material, tree stumps and features. The artifacts recovered were primarily middle- to late-19th century farm and home materials.

The archaeological investigation of the property purchased by Bernard Rell was limited in scope and resources. Archaeologists had less than five days to dig test pits and expand the units that yielded significant material. The artifacts recovered and features revealed during the investigation support the historic record of colonial occupation and a steady improvement of the property during the Updegraff’s ownership. Although the original homestead has been destroyed, one historic structure remains – the log granary. According to its owner, heavy traffic along Reach Road negatively affects the small log structure. The recommended preservation plan by the City of Williamsport is imperative. The structure should be removed and preserved as a legacy of pioneer days in Lycoming County.

Works Consulted

Baldia, Maximilian O. 2004. The Paleo-Indian Period. 28 August 2000, Rev. 20 April 2004. http://www.comp-archaeology.org/USPaleo-Indian.htm 6/01/04

Bergman, Christopher, Doershuk, John, Moeller, Roger, LaPorta, Philip, and Schuldrenrein, Joseph. 1998. An Introduction to the Early and Middle Archaic Occupations at Sandts Eddy. In: Raber, Paul A, Miller, Patricia E., Neusius, Sarah M., eds. The Archaic Period in Pennsylvania: Hunter-gatherers of the Early and Middle Holocene Period. (Recent Research in Pennsylvania Archaeology No. 1). Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Pp. 45-76.

Bressler, James P. 1989. Prehistoric Man on Canfield Island: (36LY37) Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. Williamsport, Pa.: Presto Print.

Bressler, James P. and Rainey, Harry D. 2003. Excavation of the Snyder Site (36LY287). Williamsport, Pa.: North Central Chapter No. 8, Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology and Lycoming County Historical Society.

Bressler, James P. and Rockey, Karen. 1997. Tracking the Shenks Ferry Indians at the Ault Site (36LY120). Montoursville, Pa.: Paulhamus Litho, Inc.

Carr, Kurt W. 1998. Archaeological Site Distributions and Patterns of Lithic Utilization During the Middle Archaic in Pennsylvania. In: Raber, Paul A, Miller, Patricia E., Neusius, Sarah M., eds. The Archaic Period in Pennsylvania: Hunter-gatherers of the Early and Middle Holocene Period. (Recent Research in Pennsylvania Archaeology No. 1). Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Pp. 77-90.

Carr, K.W. and Adovasio, J.M. 2002. Paleoindians in Pennsylvania. In: Carr, Kurt W. and Adovasio, James M., eds. Ice Age Peoples of Pennsylvania. (Recent Research in Pennsylvania Archaeology No. 2). Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, pp. 1-50.

Gardner, W. M. 1989. An Examination of Cultural Change in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene (ca. 9200 to 6800 BC). In: Wittkofski, J.M. and Reinhart, T. R., eds. Paleoindian Research in Virginia: A Synthesis. (Special Publication No. 19. Archaeological Society of Virginia.) Pp. 5-51.

Kelly, Kim M. 1996. The Dalton Gang. Indian Artifact Magazine. Vol. 15-1, Jan/Feb/Mar 1996: 16-17.

Miller, Patricia E. 1998. Lithic Projectile Point Tehcnology and Raw Material Use in the Susquehanna River Valley. In: Raber, Paul A, Miller, Patricia E., Neusius, Sarah M., eds. 1998. The Archaic Period in Pennsylvania: Hunter-gatherers of the Early and Middle Holocene Period. (Recent Research in Pennsylvania Archaeology No. 1). Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Pp. 91-120.

Raber, Paul A, Miller, Patricia E., Neusius, Sarah M. 1998. The Archaic Period in Pennsylvania: Current Models and Future Directions. In: Raber, Paul A, Miller, Patricia E., Neusius, Sarah M., eds. The Archaic Period in Pennsylvania: Hunter-gatherers of the Early and Middle Holocene Period. (Recent Research in Pennsylvania Archaeology No. 1). Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Pp. 121-137.

Stewart, R. Michael. 1994. Prehistoric Farmers of the Susquehanna Valley: Clemson Island Culture and the St. Anthony Site. (Occasional Publications in Northeastern Anthropology, No. 13). Bethlehem, Conn.: Archaeological Services.

Turnbaugh, William A. 1975. Man, Land, and Time: The Cultural Prehistory and Demographic Patterns of North-Central Pennsylvania. Evansville, Ind.: Unigraphic, Inc.

Wallace, Paul A.W. 1999. Indians in Pennsylvania. (Anthropological Series No. 5). 2nd ed. Rev. by William A. Hunter. Harrisburg, Penna.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.