Artisan Shawn Gardner, of Fair Chase Designs, presents on prehistoric technology and Native American art. His presentation is suitable for people of all ages, including families and school-aged children.

Gardner lives in Montoursville and often presents programs to people who visit his teepee on school field trips. He also offers seminars and classes. Gardner specializes in making custom bows, arrows, quivers, antlers, and bone carvings, and jewelry of horn, wood, stone, and silver. Utilizing prehistoric methods, he manufactures drums and musical instruments, makes birch bark baskets and other containers, hunts and processes animal hides, knaps flint, and manufactures stone tools and weapons.

Gardner presents a wealth of interesting items, making his presentation both educational and entertaining.

Flintknapping

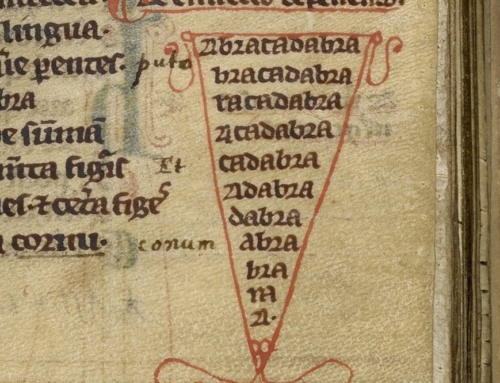

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian, or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing walls, and flushwork decoration.

According to Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia, flintknapping, also known as knapping, is performed in various ways depending on the intended purpose of the final product. For stone tools and flintlock strikers, chert is worked using a fabricator such as a hammerstone to remove lithic flakes from a nucleus or core of tool stone. Stone tools can then be further refined using wood, bone, and antler tools to perform pressure flaking. For building work, a hammer or pick is used to split chert nodules supported on the lap. Often, the chert nodule is split in half to create two cherts with a flat, circular face for use in walls constructed of lime. More sophisticated knapping is employed to produce almost perfect cubes, which are used as bricks.

Tools

There are various methods for shaping stone into useful tools. Early knappers could have used simple hammers made of wood or antlers to shape stone tools.

Hard hammer techniques are used to remove large flakes of stone. Early knappers and hobbyists replicating their methods often use cobbles of very hard stone, such as quartzite. Flintknappers can use this technique to remove broad flakes that can be made into smaller tools. This method of manufacture is believed to have been used to create some of the earliest stone tools ever discovered, some of which date back over 2 million years.

Soft hammer techniques are more precise than hard hammer methods of shaping stone. Soft hammer techniques enable a knapper to shape a stone into various types of cutting, scraping, and projectile tools.

Pressure flaking involves removing narrow flakes along the edge of a stone tool. This technique is often used to do detailed thinning and shaping of a stone tool. Pressure flaking involves putting a large amount of force across a region on the edge of the tool and (hopefully) causing a narrow flake to come off the stone. Modern hobbyists often use pressure flaking tools with a copper or brass tip, but early knappers could have used antler tines or a pointed wooden punch; traditionalist knappers still use antler tines and copper-tipped tools. The significant advantage of using soft metals rather than wood or bone is that the metal punches wear down less and are less likely to break under pressure.

Uses

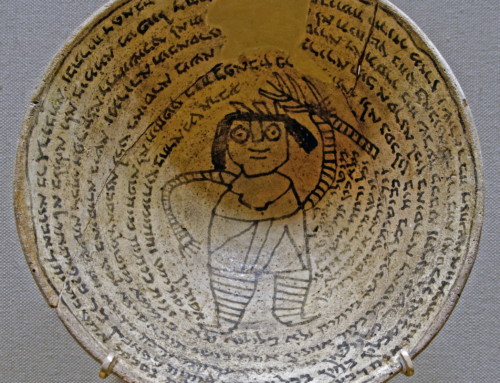

In cultures that have not adopted metalworking technologies, the production of stone tools by knappers is common, but in modern cultures, the making of such tools is the domain of experimental archaeologists and hobbyists. Archaeologists typically undertake this task to gain a deeper understanding of how prehistoric stone tools were made.

Outdoorsmen often learn knapping as a survival tactic. Knapping for the supply of strikers for flintlock firearms was a significant industry in flint-bearing locations, such as Brandon in Suffolk, England, where knappers made strikers for export as late as 1947.

Knapping for building purposes is still a skill that is practised in the flint-bearing regions of southern England, such as Sussex, Suffolk, and Norfolk, and in northern France, especially Brittany and Normandy, where there is a resurgence of the craft due to government funding.

(SOURCE: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flintknapping)