America in the 1870s was rife with labor strife and turbulence. The lumber camps and sawmills of the Williamsport area were no exception.

In 1872, Williamsport’s “lumber boom” was in full flower and great fortunes were being made by a select few.

Unfortunately, the great wealth did not make its way to the working men who helped to bring this great moneymaking resource to market. The lumber workers were poorly paid. They faced many hazards like injury and death without compensation, as there were no workmen’s compensation or death benefits available.

Marshall Anspach writes in an article about the Sawdust War that appeared in “Now and Then,” the Journal of the Muncy Historical Society, “injury or death was simply a risk they had assumed.” It was with this as a backdrop that the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law with no enforcement provisions in it for an eight-hour day for workers in May of 1868.

In May 1872, the State Labor Reform Convention was held at the Court House in Williamsport. It was a convention of labor organizations formed in 1871 and served as the impetus for the beginning of labor agitation among lumber workers. Local union activity soon commenced and, among others, was led by Thomas Greevy, a forebear of retired Judge Charles Greevy.

At a union meeting on June 26, 1872, the gathered workmen passed a resolution demanding a 10-hour-work day.

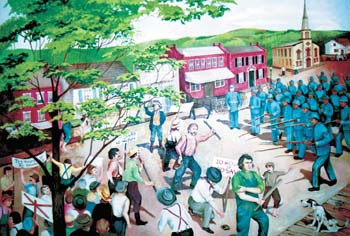

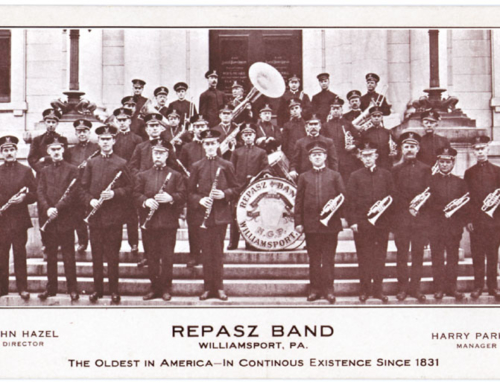

Several months previously the men who controlled the lumber trade had formed the Lumbermen’s Exchange, a cartel set up to control and monopolize lumber affairs with one voice. The Lumbermen’s Exchange answered this threat to their power by refusing to negotiate with the workmen but instead, started retaliating against them. Mayor Starkweather of Williamsport dismissed one policeman, James S. Bermingham, because of his involvement with the union. The union members refused to work at the mills. Their slogan was “Ten Hours or No Sawdust.” They marched with banners and drums beating.

There was a buildup of tension that included a call by the mayor and the county sheriff to Pennsylvania Governor James Geary that martial law should be declared and the state militia called out. He initially refused this request. The strike leaders claimed that they were not on strike but were only seeking the rights due them. Negotiations continued and there were some cracks in the “Exchange’s” resolves. Peter Herdic and several other members of the Exchange supported the 10-hour demand. The Lumbermen’s Exchange chose to close all of the mills, as well as the Susquehanna Boom. On July 22, the mill owners decided to open the mills, which started a confrontation with the strikers that included isolated acts of violence. Troops were finally called out and the number would swell to approximately 500. These troops included two Williamsport militia companies: the Williamsport Greys and the all-Black Taylor Guards, led by 1st Sgt. Jim Washington, an ex-slave. The militia companies marched on the angry crowd of strikers with fixed bayonets, which induced the strikers to disperse.

The strike leaders, Thomas Greevy, A.J. Whitten, Thomas Blake and James Bermingham, were arrested. Newspaper accounts of the time seemed sympathetic to the strikers’ plight, which had a positive outcome for those arrested. There was a large protest meeting held at the Court House on July 30, urging release of those arrested. Beginning on September 3, those jailed were tried. The men were found guilty following a short trial, and sentenced to one year of hard labor. On the day that their sentences were supposed to begin, Gov. Geary intervened, and they were given a full and complete pardon. The pardon message cited a petition with over 2,000 signatures on it that had urged Geary to pardon the men. It is speculated that Peter Herdic, who supposedly had great influence with Geary, was also partly responsible for the pardon.

This first attempt to organize lumber workers failed and it would take until the early years of the 20th Century before any attempts at organizing labor in Lycoming County would be successful. The lumber labor disorder in Williamsport foreshadowed the bloodier and more costly labor strife that would erupt in the anthracite coal fields in northeastern Pennsylvania in the mid and late 1870s, which was highlighted by the Molly Maguires and their attempts to gain economic justice for coal miners.

By Lou Hunsinger Jr., Williamsport Sun-Gazette