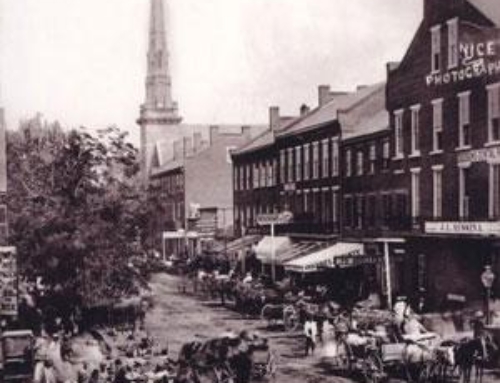

While Michael Ross was settling the City of Williamsport, selling parcels of land to frontier families and immigrants, another enterprising resident of the West Branch Valley was being hoodwinked from her home and business.

Catherine Smith, an old woman “of great business tact and energy,” had erected gristmills and sawmills on White Deer Creek. According to John F. Meginness’ “History of Lycoming County,” Smith “was a child of sorrow and affliction.”

She was left a widow with 10 children with no visible means to support her family except for 300 acres of forested land, which included the mouth of White Deer Creek. “There was a good mill seat at this point, and as a grist and saw mill were much wanted, she was often solicited to erect them,” Meginness writes.

The mills, completed in 1774-75, “were of great advantage to the county; and the following summer, she built a boring mill where great numbers of gun barrels were bored for service in the Revolutionary army.”

Smith is considered a patriot because of her rifle-boring business and because she lost a son — “her greatest help” — during the conflicts. In 1779, marauding Indians burned her mills. Katharine W. Bennet, in her “Stories of the West Branch Valley,” writes that Smith “returned to view the ruins wrought by war. The pioneers urged her to rebuild the grist and saw mills.”

After much difficulty, she raised the money needed and, in 1783, rebuilt the mills. Before her business was under way, however, the firm of Claypool and Morris claimed a prior right to the land and brought ejection notice against her. “As frequently happened,” Bennet writes, “the land office had given several warrants for the same tract, and the Claypool and Morris patent bore the earlier date.”

Prominent residents and soldiers interceded on her behalf, and the widow walked to Philadelphia and back 13 times — in her bare feet — to plead her case. According to Dr. Lewis E. Theiss in a 1950 speech to the Muncy Historical Society, “As I gather from other sources, the lawyers repeatedly double-crossed her. A hearing would be set for a given date. The troubled widow would take off her shoes and walk the 170 or so miles to Philadelphia in her bare feet. She could not afford to wear out her shoes — probably she had but one pair. She put them on at the last minute. The pioneers habitually went to church in the same way. When she got to court, the case had been postponed. There was nothing to do but trudge back home — barefooted.”

Theiss contends “there was a lot of fraud about land sales then. Indeed, when Ole Bull purchased the land for his colony of Norwegians up in the Coudersport region, well into the 19th century, he was defrauded and lost the entire tract of land, just as Catherine Smith lost her land.”

No compromise was reached and, according to Bennet, “In spite of the justice of her claims and the efforts of her friends, the case was decided against her. In 1801, she gave up possession of the property that she had labored so hard to improve.”

There was, however, one way to retain her property, writes Col. Henry W. Shoemaker in a “Now and Then” column printed Oct. 26, 1934, in the Williamsport Sun.

“On one of her first trips to Philadelphia, she was accompanied by her beautiful daughter, Cassandra, who created a sensation, when she entered Independence Hall,” Shoemaker writes. “Of the same witching, dark-eyed type as her mother had been in her youth, with the proud coronet features, she was a head taller than the old lady. She won the hearts of the susceptible legislators. It was asserted that one of the Claypool, a man of 45, wished to become the husband of Cassandra Smith. For this, he would quash the firm’s claims and restore the property.

Shoemaker continues, “The lonely 22-year-old girl was willing to marry him, in order to see her mother made happy. But the stern old Roman matron refused this patrician alliance for her daughter and the return of her property by any ‘left-handed bargain,’ as she called it, and continued to fight her petition on to its final inglorious end.”

Widow Smith died in poverty and was buried in the ancient settler’s graveyard at the corner of Daniel Caldwell’s barn.

In making improvements years later, the farmer leveled the graveyard with the plow. Smith’s bones were disturbed, and those who knew her well recognized her skull — on account of its protruding teeth.

“There is something unspeakably pathetic in the history of this woman,” Meginness concludes. “Her struggles in widowhood; what she accomplished for the benefit of early settlers; the fact that she furnished a mill for the manufacture of gun barrels to aid in the achievement of our liberties; her misfortunes and her last appeal to the law-making power for assistance; her death, burial and the final disturbance of her bones, afford a theme for a volume.”

In recognition of her heroism, a state commission selected a natural memorial to the Widow Smith and named the “noble culmination of Nittany Mountain, which looks down on the spot where she passed her most eventful and memorable days, “Catherine’s Crown,’ ” Shoemaker writes.

For her “relentless pursuit of righteousness, her lofty ideals and heroic efforts in the cause of freedom,” Shoemaker writes, and “though she was poor and obscure and had few educational advantages . . . she deserves a place among the seats of the might, right beside the greatest women of the land.”

By Robin Van Auken, Williamsport Sun-Gazette