During the tumultuous years leading up to the French and Indian War, early settlers in Northcentral Pennsylvania had two choices: They could leave the fertile valleys of the Susquehanna or take their chances with sporadic American Indian raids during which farms were destroyed and entire families would be slaughtered.

Although the Iroquois Confederacy maintained a peaceful relationship with the English, other American Indian tribes allied with the French explorers and were interested in retaining the booming fur trade.

The fur trade was the most important activity in the Province, A.G. Zimmerman writes in “The Indian Trade of Colonial Pennsylvania.”

“If one were to survey all of the space given Indian affairs in the records of the Council, of the Assembly and in the papers of the Governor, it would dwarf in importance any other topic,” Zimmerman writes. “And Indian policy and the establishment of good relations with the natives was inexorably tied to trade.”

The French, fearing the loss of the fur trade, built a chain of forts in 1753 along the Allegheny River in Pennsylvania on land the British also claimed. In the spring of 1754, the British retaliated and began to build a fort at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers. As they finished their task, a sizeable French flotilla appeared around the bend, and the British had to yield. The French built a larger fort on the site, Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh).

Penn’s Creek Massacre

According to 19th-century historian John F. Meginness, Penn’s Creek settlers were the first to experience “the effects of Indian vengeance” on Oct. 15, 1755. Frustrated with white settlers who continued to work their way westward, “a hostile body of savages, painted and clad in war costume, descended the West Branch and fell upon the Penn’s Creek settlements,” Meginness writes.

Every person in the settlement – 25 men, women, and children – was either killed or carried into captivity. The cabins were burned, stock slain, and fields laid waste, Meginness reports.

“We are particular in noting this first massacre, for it marks the beginning of the long French and Indian War which followed, and in which the settlers of this portion (present-day Lycoming County) suffered so severely,” Meginness writes. “The Indians who made this foray were from the Allegheny and were induced to come here by the French, who were flushed with their victory over (Gen.) Braddock.”

The massacre was the first to occur in the Province of Pennsylvania east of the Alleghenies and struck terror in the other settlements along the river.

Two weeks later, Andrew Montour, son of the famed Madam Montour, and old Chief Monagatootha were sent for by a band of Delaware and Shawanese American Indians to a spot east of Lock Haven. They informed the two of plans by the French to kill settlers and asked them to unite in a war against the English. Montour and Monagatootha declined.

According to Meginness, Montour reported this intelligence to Gov. Robert H. Morris; however, the governor was indifferent to frontier conflicts.

Declares War

After repeated attacks on settlers and continued unrest, Gov. Morris, on April 14, 1756, issued a declaration of war against the Delaware tribe of American Indians and “others in confederacy with them,” Meginness writes.

The declaration of war, Zimmerman counters, was economically motivated, not because of murdered settlers.

“From the Mother County’s point of view, Indian affairs are the most important type of entry listed . . . and the conflict with the French in the Ohio Valley, brought about by the Pennsylvania trader, triggered for Britain a world-wide war effort,” Zimmerman writes.

Killingng Mandated

Gov. Morris issued a statement warning the Delaware American Indians and their associations they were considered “enemies, rebels, and traitors to His Most Sacred Majesty” and required all subjects of the province to pursue and kill them.

He posted a “Reward for Indian Scalps,” Meginness writes, “thinking no doubt that bombast would immediately frighten the Delawares into peaceful submission.”

The announcement caused much excitement among the people, and in particular, it distressed the Quakers “whose sympathies were with the savages,” Meginness reports.

Meginness claims Morris’ proclamation “was too bombastic to have a good effect, and had he ordered defensive movements sooner and threatened less, he might have accomplished more important results and saved many a white settler. As it was feared, his proclamation only intensified the vindictive feelings of the Indians and caused them to commit greater atrocities.”

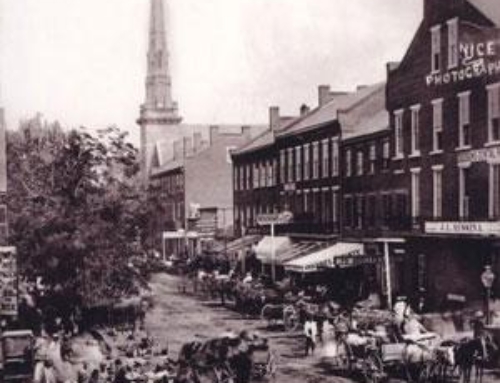

The British began work on Fort Augusta, Meginness writes, which “became an important factor in the early settlement of the West Branch region, and the place of refuge for may a settler flying from what is now Lycoming County to escape the … knife.”

He continues, “(Lycoming County) was constantly infested with roving bands of savages bent on pillage and murder.”

The Battlefield

Present-day Lycoming County was far removed from the battlefields of recent history, yet the French considered the West Branch Valley a vital route and attempted an invasion here.

Before Fort Augusta was completed, Marquis de Vaudreuil recorded a French expedition to overtake the fort on July 13, 1757, and it is in the Archives of France.

French soldier M. De St. Ours, along with six Canadians and 14 American Indians, traveled down the Susquehanna to the mouth of the Loyalsock. A scouting party attacked two people outside Fort Augusta. But, overawed by reports of the garrison’s strength, the invaders withdrew without formally attacking. They purportedly dumped their cannon downstream of the Loyalsock.

According to Meginness, archaeological evidence supports the brief stay of French in the area.

Horrific Origins

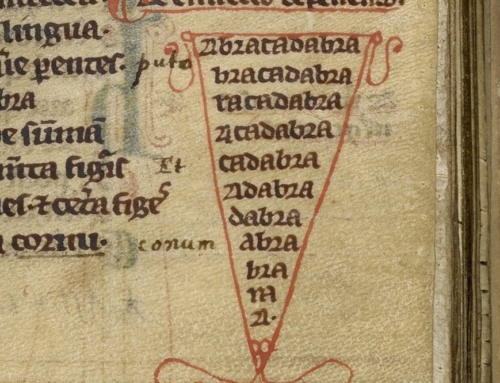

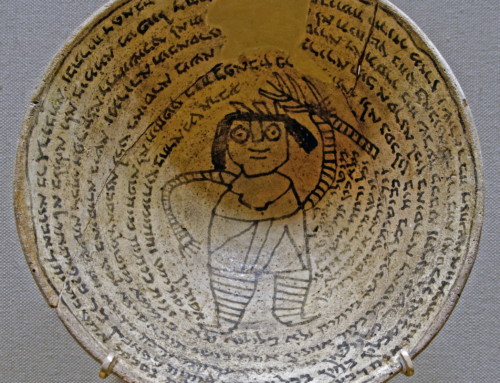

According to George A. Bray III, in ” Scalping During the French and Indian War,” history is replete with incidents by French, English, and American Indian combatants.

He writes: “Scalping, of course, predated the mid-18th century. Historical records, archaeology, and other sciences strongly indicate the practice originated among certain Native American tribes.”

Bray found the memoirs of a French soldier, identified by the initials J. C. B.

“When a war party has captured one or more prisoners that cannot be taken away, it is the usual custom to kill them by breaking their heads with the blows of a tomahawk. When he has struck two or three blows, the savage quickly seizes his knife and makes an incision around the hair from the upper part of the forehead to the back of the neck. Then he puts his foot on the shoulder of the victim, whom he has turned over face down, and pulls the hair off with both hands, from back to front. This hasty operation is no sooner finished than the savage fastens the scalp to his belt and goes on his way. This method is only used when the prisoner cannot follow his captor. When a savage has taken a scalp and is not afraid he is being pursued, he stops and scrapes the skin to remove the blood and fibers on it. He makes a hoop of greenwood, stretches the skin over it like a tambourine, and puts it in the sun to dry a little. The skin is painted red, and the hair on the outside combed. When prepared, the scalp is fastened to the end of a long stick and carried on his shoulder in triumph to the village or place where he wants to put it. But as he nears each place on his way, he gives as many cries as he has scalps to announce his arrival and show his bravery. Sometimes as many as 15 scalps are fastened on the same stick. When there are too many for one stick, they decorate several sticks with the scalps.”

Bray continues: “Another Frenchman, Captain Pierre Pouchot, of the Bearn Regiment, and commandant at Fort Niagara most of the war, recounted in his memoirs how the Native American would scalp his foe. ‘As soon as the man is felled, they run up to him, thrust their knee in between his shoulder blades, seize a tuft of hair in one hand and, with their knife in the other, cut around the skin of the head and pull the whole piece away. The whole thing is done very expeditiously. Then, brandishing the scalp, they utter a whoop, which they call the death whoop. If they are not under pressure and the victory has cost them lives, they behave in an extremely cruel manner towards those they kill or the dead bodies. They disembowel them and smear their blood all over themselves.”

It is important to remember, Bray writes, that while Europeans did not originate scalping, they did encourage its spread by establishing bounties and “the French and English were accustomed to pay for the scalps, to the amount of 30 francs’ worth of trade goods. Their purpose was then to encourage the savages to take as many scalps as they could and to know the number of the foe who had fallen.”

Rewards for American Indian Scalps

The French paid virtually nothing for scalps, preferring to purchase prisoners that they would, at times, send back to their families or utilize for prisoner exchanges. Father Pierre Joseph Antonie Roubaud, missionary to the Abenaki at St. Francis, obtained a scalp from one of his warriors to redeem an infant from a Huron captor. The priest then reunited the baby with his parents.

The English, however, passed acts through their colonial assemblies. Even before war was declared and before Gov. Morris offered to pay for scalps, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley offered #40 for American Indian male scalps and #20 for female scalps.

Some entrepreneurs came up with the idea of making them horsehide, which they prepared like human scalps. The discovery of this fraud was why they were more carefully inspected before a payment was made.

Another problem was that friendly American Indians were often killed, generally from behind and unawares, for the price of scalps.

Consequently, the French and English finished by giving only a negligible amount of presents.

Surviving an Attack

Bray notes that there were people who survived the experience.

The New York Gazette, July 30, 1759, carried an article proclaiming that as proof that “many persons have survived after being scalped, we can assure our readers, that four Highlanders are lately arrived from America, for admission into Chelsea Hospital, who had been scalped and left for dead.”

Warren Johnson declared in his journal on April 12, 1761, that “there are many instances of both men and women recovering after being scalped.” He also confirmed scalps were pulled “off from the back of the head.”

The New York Mercury reported that about June 8, 1759, “two of our battoes were attacked on their way up the Mohawk’s River, by a party of the enemy. The same party a day or two after scalped a woman, and carried off a child and a servant that were in company, between Fort Johnson and Schenectady; the woman lived ’til she got into Schenectady, tho’ in great agony.”

French-allied American Indians skulked about British forts to inflict what casualties they could. Stephen Cross, a shipbuilder from Massachusetts, records on May 25, 1756, that “one of our soldiers came in from the edge of the woods, where it seems he had lain all night having been out on the evening party the day before and got drunk and could not get in, and not being missed, but on seeing him found he had lost his scalp, but he could not tell how nor when, having no others around. We supposed the Indians had stumbled over him in the dark, and supposed him dead, and taken off his scalp.”

By Robin Van Auken, Williamsport Sun-Gazette