The spirit of Rachel Carson lives on, instilling in the Earth’s human population awareness of its fragile environment and an urgency to protect it from toxins.

Although it’s been five decades since the publication of her runaway bestseller, “Silent Spring” (1962), Carson remains one of the greatest nature writers of America and one of America’s Top 100 Scientists according to a Time magazine poll.

“The beauty of the living world I was trying to save,” she wrote in a letter to a friend in 1962, “has always been uppermost in my mind — that, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done. I have felt bound by a solemn obligation to do what I could — if I didn’t at least try I could never be happy again in nature. But now I can believe that I have at least helped a little. It would be unrealistic to believe one book could bring a complete change.”

A Naturalist Is Born

Born May 27, 1907 in Springdale, Pa., Carson graduated from Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham College) in 1929, studied at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory, and received her master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932. While attending the university, she was published in the Baltimore Sun.

She began a 15-year career in federal service as a scientist and editor in 1936 and rose to become editor-in-chief of all publications for the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Her first book, “Under the Sea Wind” (Oxford University Press 1941), was published just before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Lost in the tide of war, the book was largely overlooked.

Her next book, “The Sea Around Us” (Oxford University Press 1951), was first serialized in The New Yorker, and caused such a stir that it became a bestseller when finally printed. It was followed by “The Edge of the Sea” (Houghton Mifflin Company 1955) and then by “Silent Spring” (Houghton Mifflin Company 1962).

As early as 1945, Carson had become alarmed by government abuse of chemical pesticides (such as DDT) and pest-control programs that poisoned with little regard for the welfare of other animals.

“The more I learned about the use of pesticides, the more appalled I became,” Carson recalled. “I realized that here was the material for a book. What I discovered was that everything which meant most to me as a naturalist was being threatened, and that nothing I could do would be more important.”

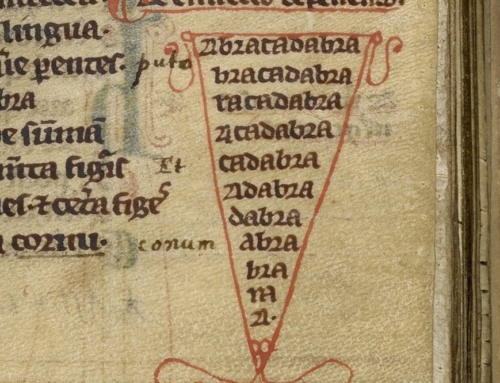

Carson eloquently penned her dire warnings in “Silent Spring”: “There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings . . . Then a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change . . . There was a strange stillness . . . The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices.”

In a vile attack to undermine Carson, chemical companies and the U.S. Department of Agriculture had only increased public awareness. “Silent Spring” became a bestseller and is regarded as the cornerstone of the new environmentalism. Sense of Wonder Carson died in 1964 at the age of 56 following a long struggle with breast cancer, but her enduring love and wonder for the universe — and her ability to provoke the same sense in others — was posthumously published in New York.

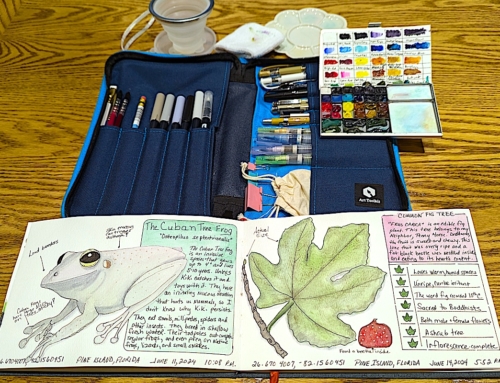

“The Sense of Wonder,” by Carson with photographs by Charles Pratt (Harper & Row 1965), encourages adults to endow every child with “a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life.” Her narrative charts a path for adults and children to take together on a journey of discovery — the same path she took with her grandnephew, Roger, to whom the book is dedicated.

In her book, “The Sense of Wonder,” Carson encourages parents and other adults to overcome their sense of inadequacy when confronting the complex natural world and instead concentrating on how they “feel” instead of what they “know.” “If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder without any such gift from the fairies, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in,” she writes. “It is more important to pave the way for the child to want to know than to put him on a diet of facts he is not ready to assimilate.”

What are you waiting for? Go outside and reawaken your own sense of wonder.