National Archives Releases

Civil War Documents, Photograph

Interested in the ephemera of the Civil War?

The National Archives has released thousands of documents and photographs from the American Civil War, and Wikimedia Commons is organizing them.

Here’s just one of many photos of U.S. History in the category: Virginia, Army of the Potomac Headquarters. Captain Harry Page, Quartermaster. This photograph, “The Halt,” was taken by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, a noted young photographer who began his career during the American Civil War.

O’Sullivan was born in Ireland in 1840, and immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1842. As a teen, he met Mathew Brady and was employed at the photographer’s New York City studio. In 1861, the Civil War began, and O’Sullivan joined the Union Army. He was honorably discharged after a year, and he rejoined Brady’s photographic team. Soon, however, he left Brady’s studio to photograph battlefields on his own.

O’Sullivan photographed the 1862 campaign of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Northern Virginia Campaign. At this time, he joined Alexander Gardner’s studio, and published 44 photographs in “Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War,” the first photographic collection of the Civil War. Gardner’s studio photographed many battlefields, including Antietam.

“Harvest of Death,” Gettysburg Battle, by Timothy O’Sullivan.

In July 1863, he photographed the horrific aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, and from this printed his most famous photograph, “The Harvest of Death.”

The year 1864, found O’Sullivan on the trail of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to capture the historic moment of the Siege of Petersburg. O’Sullivan next traveled another siege — that of Fort Fisher in Wilmington, North Carolina. The fall of the fort meant the Confederacy’s last remaining sea port was lost. The South was cut off from global trade.

O’Sullivan traveled next to Appomattox Court House, where Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant in April 1865.

Following the Civil War, O’Sullivan became the official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel. His assignment was to attract settlers to the expanding West. In this capacity, O’Sullivan helped pioneer “geophotography.”

Timothy H. O’Sullivan with imprint of F.G. Ludlow, Carson City, Nevada Territory on verso. Taken between 1871-74 while O’Sullivan was the official photographer for the Wheeler Expedition.

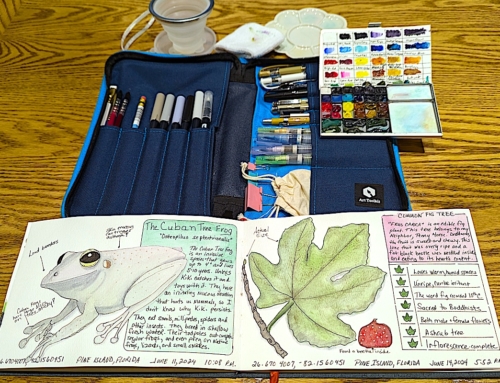

O’Sullivan also took the earliest photographs of prehistoric Native American ruins and pueblo villages of the Southwest. His photographic process, according to the U.K. Daily Mail, was to use “a primitive wet plate box camera which he would have to spend several minutes setting up every time he wanted to take a photograph. He would have to assemble the device on a tripod, coat a glass plate with collodion – a flammable solution. The glass would then be put in a holder before being inserted into a camera. After a few seconds exposure, he would rush the plate to his darkroom wagon and cover it in chemicals to begin the development process.”

His next big adventure came in 1870, as part of a team in Panama to survey for a canal across the isthmus.

O’Sullivan returned to the Southwest in 1871 to 1874, joining Lt. George M. Wheeler’s survey west of the 100th meridian west. As part of this survey team, he and his team faced hardships and starvation along the Colorado River after they capsized. A greater tragedy than near starvation is that only a few of his 300 glass-plate negatives survived the trip to Washington, D.C., where his next role was to serve as official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department.

O’Sullivan died young, of tuberculosis at age 42.