So, what does a forty-five-foot tall, forty-one-ton monument on private land, the Susquehannock Indians, an ex-bank president in Indian dress-up, and a magical place called Lockabar have in common? Well, historian Carl Becker once said it best, “history is an imaginative creation” and that tongue-in-cheek remark never bore more truth than the story of the King Widaagh Monument in Nippenose Township, PA.

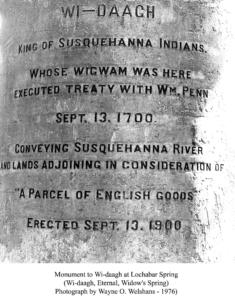

When I first saw the monument (yes the monument is one of the real parts), I was taken aback by its presence near a dirt driveway on private property. It is, in short, amazing and unexpected. When I read the inscription, I was equally flabbergasted:

Now, I pride myself on knowing a little bit about Pennsylvania’s history, and this, I’ve gotta tell you, did not make sense. The Susquehannock Indians (the monument says Susquehanna Indians, which was a common duo usage) were a defeated people by that date, having been conquered by the mighty Five Nations of the Iroquois from New York State. In 1675, they were defeated in the Lancaster area of Pennsylvania and then driven into Maryland and Virginia. With the presence of fierce Indian warriors so close to them, the Colonials were nervous enough to send in the militia. It was clear to the refugee Susquehannocks that they would not be safe where they were trying to resettle. It must have been a bitter pill to swallow but they had little choice but to petition the Iroquois for admittance back into Pennsylvania.

Though they sometimes waged relentless and total war on their enemies, once defeated, the Iroquois many times would adopt their foes into their villages and allow those defeated to live on their lands as subjects. Anthropologists believe some Iroquois towns were ninety percent non-Iroquois because of this policy. So, it was with the Susquehannocks. They would settle in a few select locations in their previous southern Pennsylvania lands; however, all territory owned by the Susquehannocks, which was virtually all of Pennsylvania, became Iroquois Lands.

The William Penn part of the inscription was equally confusing. I’m familiar with the various land acquisitions by the Penn family and I had never heard of this one. The early date, the location of this conveyance, and land purchased from a subjugated people made it difficult to believe that it was anything other than a local legend. I said as much to a few people, including Tina Cooney, president of the Jersey Shore Historical Society, but I told her that I would continue to research.

The William Penn part of the inscription was equally confusing. I’m familiar with the various land acquisitions by the Penn family and I had never heard of this one. The early date, the location of this conveyance, and land purchased from a subjugated people made it difficult to believe that it was anything other than a local legend. I said as much to a few people, including Tina Cooney, president of the Jersey Shore Historical Society, but I told her that I would continue to research.

Now eating humble pie has never been my strong suit, nevertheless, a humbling experience awaited me while searching the Pennsylvania Archives. Working late in the evening on Christmas Eve when not a mouse was stirring tells you two things about me — I’m like a bloodhound and I have no life. Awaiting me in those pages including the Provincial Council Minutes for Sept. 13, 1700, was a confirmation that the purchase and those involved were actually true: William Penn, Wi-Daagh, the initial treaty of 1700, and the whole shootin’ match. However, as they say, stay tuned for the rest of the story.

Thomas Dongan, Earl of Limerick and former governor of New York, was the key to the whole story. Until he came into view as a player, my research was going nowhere. While in office and after the ruin of the Susquehannocks he purchased, for lack of better words, a right-of-way through the entire Susquehanna drainage with lands on both sides. The purchase was made from his friends, the Iroquois. In turn, he offered these lands to William Penn. Penn also wanted a right of way into lands that had not been purchased yet. He paid the ex-governor his asking price and sent emissaries to the Iroquois looking to validate the purchase. Almost immediately however the Iroquois complained that this was not proper. Pennsylvania was theirs by right of conquest and not to be traded or conveyed to others without consent. They launched a protest with Colonial provinces that would last for years.

Despite the disapproving Iroquois, on April 23, 1701, Philadelphia would be the site of what would become the validation ceremony for the big purchase. In my opinion, the whole affair was not typical of William Penn’s treatment of treaties or, for that matter, any other aspect of dealings with Native Americans. However, I do see a man who seems desperate to make this happen. Maybe it was the price paid to Thomas Dongan or the importance of being able to access the interior of what would become Pennsylvania. Either way, it seems a little on the shady side or I might be kind in that evaluation, it might have been a lot on the shady side. The records do not say what a parcel of English goods amounted to but it doesn’t seem like much, even as a token payment to the Indians.

In the later part of the 1600s, the last of the Susquehannocks living in Pennsylvania become widely known by the Colonials as the Conestoga Indians. It is theorized that the name Conestoga was a corruption of what they called themselves, the Gandastoga. The Conestoga people were concentrated in Lancaster County near their ancestral lands and numbered only about 300 souls. These were the remnants of Widaagh’s people. His mark does appear on the land treaty and provincial delegates crowned him King Widaagh.

So, most everything written on the column was true and happened as stated but this is where the legend begins.

The location of the monument is called Lockabar. This is not an Indian place name but is Gaelic and named after a location in the west highlands of Scotland. It must have reminded someone of that region, being a spectacular bit of mountain scenery with a cave-fed pool that meets Antes Creek.

Colonel George Sanderson, one of a succession of owners, purchased the property in 1848. Sanderson was a businessman and ex-bank president and was also the person responsible for the monument. In what would seem like an unrelated incident, the Capitol building in Harrisburg burned in 1897 and had to be demolished. Sanderson purchased three of the columns supporting the structure and brought them to Lycoming County. Two were placed in local cemeteries and one was placed on his property at Lockabar where the inscription was added. On the face of things, Sanderson would seem to be a historian marking a moment in Pennsylvania’s peaceful acquisition of land from the Indians. But the embellishment and outright fantasies that abound at Lockabar would preclude that. I believe that the Improved Order of Red Men, one of the organizations Col. George Sanderson was a member of, is most likely the answer. This was a patriotic secret society that probably began as a branch of the Sons of Liberty. In his book “Nippenose Valley,” Wayne Welshans has a drawing of Sanderson and his fellow “Red Men” in Indian garb.

In 1900, the same year as the inscription was made on the monument, Uriah Cumming wrote a book titled “The Song of U-ri-on-tah” and dedicated it to Sanderson. I read what I could of the 400-page book, which included all kinds of creatures and tales of long-lost Indian ceremonies. If any of his blatherings were true, I’d be surprised. I could only conclude that it was written as a fantasy.

I enjoy local folktales and even ghost stories but I think we need to know enough of history that the lines aren’t blurred terribly. In this case, there are too many questions and red flags for anybody truly interested in the actual events.

The monument states that Widaagh’s wigwam was at Lockabar. I don’t think so. There were no white settlers in this area in 1700 who could confirm that statement. Widaagh’s grave is supposedly on the same site. I don’t think so. As far as my research has taken me, all the Susquehannocks lived a peaceful coexistence with settlers in and around Lancaster County until the last of the recognized Susquehannocks (Conestoga) were buried in a mass grave in Lancaster after the Paxton Boys hacked them to death in 1763 at the onset of Pontiac’s War. It is implied that William Penn traveled here to sign the original treaty. I don’t think so. Penn never made it further into Pennsylvania than Lancaster County. It’s a nice story that includes the Great Island at Lock Haven and other recognizable locations but it’s only a story.

However, the ghost story of Widaagh’s haunting of the valley because of his regret for selling land to the English for so little is based on some truth. The Indians’ concept of land sale was based more on the buyer passing through, hunting on, or as shared usage and not exclusive ownership. Consequently, when the Conestoga realized that the English now owned the Susquehanna River and lands on both sides, the Pennsylvania Archives does record a statement of sadness and regret from them for selling it for virtually nothing.

Perhaps it was Col. Sanderson’s intent to entertain. Mixing history with fantasy would do that. Maybe he was fulfilling some mission for his secret society and, just maybe, he thought that those in the future would easily know the difference with no harm done. Whatever his intent, his riddle has undoubtedly helped to preserved part of our state history for future generations. And while Widaagh may or may not be haunting in the Nippenose Valley, I will bet that for the last 300 years he’s been turning over in his grave — wherever that is.

By Tom “Tank” Baird

Vice President Northcentral Chapter 8 Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology

All pictures provided by Wayne Welshans author of “Nippenose Valley”.